In 1994, California voters passed initiatives to lock away repeated offenders and deny social services to undocumented immigrants. But times have changed. California is now a “sanctuary state” for those residing in the country illegally, tough on crime laws have been relaxed, and progressive lawmakers have put an end to cash bail. Is criminal justice reform the new political normal or will “tough on crime” make a comeback?

Capital punishment: In 2016, California voters passed Proposition 62, which streamlines the appeals process for inmates on death row. In the same election, voters rejected a ballot initiative that would have ended capital punishment in the state. California has only carried out 15 executions since 1978, the last one in 2006. But with the new law in place, the next governor may be asked to administer California’s first execution in over a decade.

Police shooting investigations: In March, two Sacramento Police Department officers shot and killed Stephon Clark in his grandmother’s backyard, apparently mistaking the cell phone in his hand for a gun. In response, the California Department of Justice announced that it would be overseeing the investigation into Clark’s death. For years, bills have been introduced in Sacramento that would require state oversight in all such investigations, but none have made it out of the legislature. That’s in part due to the opposition of law enforcement unions.

Sanctuary State: Under California’s recently enacted “sanctuary state” law, cops and sheriffs cannot inquire about a person’s immigration status, keep a person in custody based solely on a request from immigration authorities, help immigration agents make arrests or transfer people to federal custody without a warrant. In March, Attorney General Jeff Sessions sued California for a series of state immigration laws, including the sanctuary state law. The administration argues that California is in violation of a federal law that bans any restrictions on communication between law enforcement officers and immigration agents about an arrestee’s immigration status. California’s attorney general, Xavier Becerra, counters that the U.S. Constitution bans the federal government for requiring state law enforcement to enforce federal law.

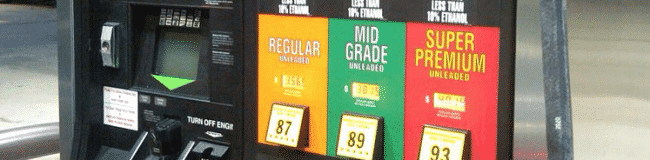

Cash bail: How do courts ensure that someone charged with a crime will show up for trial? In California, judges have historically used cash bail: the accused puts down a deposit up front and if they make to it court, they get the money back. If a defendant can’t afford the set bail amount, they can contract with a bail bond company, which will make the payment for a fee. But criminal justice reform advocates have long argued that this system penalizes the poor, while allowing the well-off to purchase their freedom. This year state lawmakers took up the call and replaced bail with an alternative system that allows judges to either keep an arrestee in jail or send them home pre-trial depending on their assessed flight risk and danger to the public.

Non-disclosure agreements in sexual harassment settlements: Over the last year, three California lawmakers have stepped down over sexual misconduct allegations. Another member of the Assembly took a leave of absence in the wake of harassment allegations, a senator was banned from giving hugs, and the Legislature has released a cache of harassment investigation records naming over a dozen employees. Some of these allegations went undisclosed to the public for years, in part because those making the allegations were bound by non-disclosure agreements. Lawmakers have banned both public and private employers from placing secrecy requirements in legal agreements related to sexual misconduct.

Policing police

by Laurel Rosenhall, CALmatters

Sanctuary state

by Elizabeth Aguilera, CALmatters

Bail

by Laurel Rosenhall, CALmatters

#MeToo

by Laurel Rosenhall, CALmatters